Stress Testing Dynamic R/exams Exercises

Motivation

After a dynamic exercise has been developed, thorough testing is recommended before administering the exercise in a student assessment. Therefore, the R/exams package provides the function stresstest_exercise() to aid teachers in this process. While the teachers still have to assess themselves how sensible/intelligible/appropriate/… the exercise is, the R function can help check:

- whether the data-generating process works without errors or infinite loops,

- how long a random draw from the exercise takes,

- what range the correct results fall into,

- whether there are patterns in the results that students could leverage for guessing the correct answer.

To do so, the function takes the exercise and compiles it hundreds or thousands of times. In each of the iterations the correct solution(s) and the run times are stored in a data frame along with all variables (numeric/integer/character of length 1) created by the exercise. This data frame can then be used to examine undesirable behavior of the exercise. More specifically, for some values of the variables the solutions might become extreme in some way (e.g., very small or very large etc.) or single-choice/multiple-choice answers might not be uniformly distributed.

In our experience such patterns are not rare in practice and our students are very good at picking them up, leveraging them for solving the exercises in exams.

Example: Calculating binomial probabilities

In order to exemplify the work flow, let’s consider a simple exercise about calculating a certain binomial probability:

According to a recent survey 100 - p percent of all customers in grocery stores pay cash while the rest use their credit or cash card. You are currently waiting in the queue at the checkout of a grocery story with n customers in front of you. What is the probability (in percent) that k or more of the other customers pay with their card? |

In R, the correct answer for this exercise can be computed as 100 * pbinom(k - 1, size = n, prob = p/100, lower.tail = FALSE) which we ask for in the exercise (rounded to two digits).

In the folllowing, we illustrate typical problems of parameterizing such an exercise: For an exercise with numeric answer we only need to sample the variables p, n, and k. For a single-choice version we also need a certain number of wrong answers (or “distractors”), comprised of typical errors and/or random numbers. For both types of exercises we first show a version that exhibits some undesirable properties and then proceed to an improved version of it.

| # | Exercise templates | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | binomial1.Rmd binomial1.Rnw |

num |

First attempt with poor parameter ranges. |

| 2 | binomial2.Rmd binomial2.Rnw |

num |

As in #1 but with some parameter ranges improved. |

| 3 | binomial3.Rmd binomial3.Rnw |

schoice |

Single-choice version based on #2 but with too many typical wrong solutions and poor random answers. |

| 4 | binomial4.Rmd binomial4.Rnw |

schoice |

As in #3 but with improved sampling of both typical errors and random solutions. |

If you want to replicate the illustrations below you can easily download all four exercises from within R. Here, we show how to do so for the R/Markdown (.Rmd) version of the exercise but equivalently you can also use the R\LaTeX version (.Rnw):

for(i in paste0(extra, 1:4, ".Rmd")) download.file(

paste0("https://www.R-exams.org/assets/posts/2019-07-10-stresstest/", i), i)Numerical exercise: First attempt

In a first attempt we generate the parameters in the exercise as:

## success probability in percent (= pay with card)

p <- sample(0:4, size = 1)

## number of attempts (= customers in queue)

n <- sample(6:9, size = 1)

## minimum number of successes (= customers who pay with card)

k <- sample(2:4, 1)Let’s stress test this exercise:

s1 <- stresstest_exercise("binomial1.Rmd")## 1/2/3/4/5/6/7/8/9/10/11/12/13/14/15/16/17/18/19/20/21/22/23/24/25/26/27/28/29/30/31/32/33/34/35/36/37/38/39/40/41/42/43/44/45/46/47/48/49/50/51/52/53/54/55/56/57/58/59/60/61/62/63/64/65/66/67/68/69/70/71/72/73/74/75/76/77/78/79/80/81/82/83/84/85/86/87/88/89/90/91/92/93/94/95/96/97/98/99/100

By default this generates 100 random draws from the exercise with seeds from 1 to 100. The seeds are also printed in the R console, seperated by slashes. Therefore, it is easy to reproduce errors that might occur when running the stress test, i.e., just set.seed(i) with i being the problematic iteration and subsequently run something like exams2html() or run the code for generating the parameters manually.

Here, no errors occurred but further examination shows that parameters have clearly been too extreme:

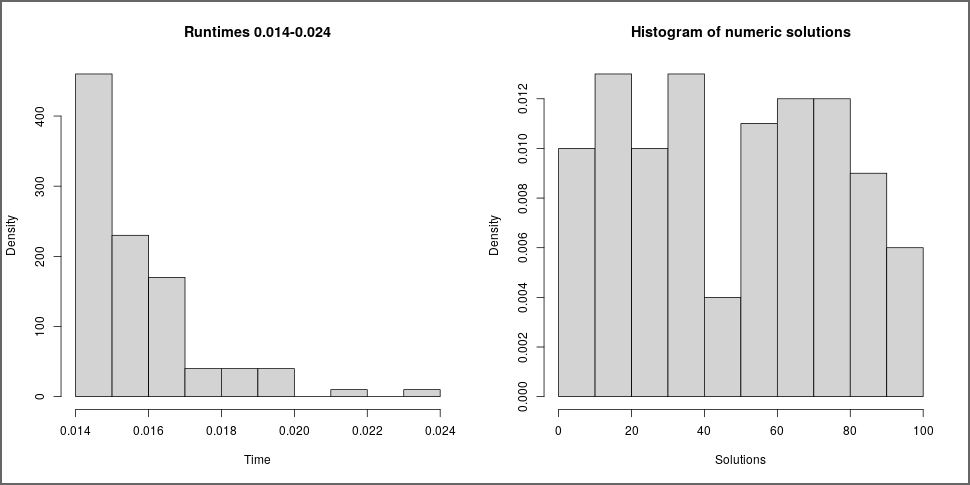

plot(s1)The left panel shows the distribution run times which shows that this was fast without any problems. However, the distribution of solutions in the right panel shows that almost all solutions are extremely small. In fact, when accessing the solutions from the object s1 and summarizing them we see that a large proportion was exactly zero (due to rounding).

summary(s1$solution)## Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

## 0.0000 0.0000 0.0200 0.5239 0.3100 4.7800

You might have already noticed the source of the problems when we presented the code above: the values for p are extremely small (and even include 0) but also k is rather large. But even if we didn’t notice this in the code directly we could have detected it visually by plotting the solution against the parameter variables from the exercise:

plot(s1, type = "solution")Remark: In addition to the solution the object s1 contains the seeds, the runtime, and a data.frame with all objects of length 1 that were newly created within the exercise. Sometimes it is useful to explore these in more detail manually.

names(s1)## [1] "seeds" "runtime" "objects" "solution"

names(s1$objects)## [1] "k" "n" "p" "sol"

Numerical exercise: Improved version

To fix the problems detected above, we increase the range for p to be between 10 and 30 percent and reduce k to values from 1 to 3, i.e., employ the following lines in the exercise:

p <- sample(10:30, size = 1)

k <- sample(1:3, 1)Stress testing this modified exercise yields solutions with a much better spread:

s2 <- stresstest_exercise("binomial2.Rmd")

plot(s2)Closer inspection shows that solutions can still become rather small:

summary(s2$solution)## Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

## 3.31 20.31 50.08 47.41 72.52 94.80

For fine tuning we might be interested in finding out when the threshold of 5 percent probability is exceeded, depending on the variables p and k. This can be done graphically via:

plot(s2, type = "solution", variables = c("p", "k"), threshold = 5)So maybe we could increase the minimum for p from 10 to 15 percent. In the following single-choice version of the exercise we will do so in order leave more room for incorrect answers below the correct solution.

Single-choice exercise: First attempt

Building on the numeric example above we now move on to set up a corresponding single-choice exercise. This is supported by more learning management systems, e.g., for live voting or for written exams that are scanned automatically. Thus, in addition to the correct solution we simply need to set up a certain number of distractors. Our idea is to use two distractors that are based on typical errors students may make plus two random distractors.

ok <- FALSE

while(!ok) {

## two typical errors: 1-p vs. p, pbinom vs. dbinom

err1 <- 100 * pbinom(k - 1, size = n, prob = 1 - p/100, lower.tail = FALSE)

err2 <- 100 * dbinom(k, size = n, prob = p/100)

## two random errors

rand <- runif(2, min = 0, max = 100)

## make sure solutions and errors are unique

ans <- round(c(sol, err1, err2, rand), digits = 2)

ok <- length(unique(ans)) == 5

}Additionally, the code makes sure that we really do obtain five distinct numbers. Even if the probability of two distractors coinciding is very small, it might occur eventually. Finally, because the correct solution is always the first element in ans we can set exsolution in the meta-information to 10000 but then have to set exshuffle to TRUE so that the answers are shuffled in each random draw.

So we are quite hopeful that our exercise will do ok in the stress test:

s3 <- stresstest_exercise("binomial3.Rmd")

plot(s3)The runtimes are still ok (indicating that the while loop was rarely used) as are the numeric solutions - and due to shuffling the position of the correct solution

in the answer list is completely random. However, the rank of the solution is not: the correct solution is never the smallest or the largest of the

answer options. The reasons for this surely have to be our typical errors:

plot(s3, type = "solution", variables = c("err1", "err2"))And indeed err1 is always (much) larger than the correct solution and err2 is always smaller. Of course, we could have realized this from the way we set up those typical errors but we didn’t have to - due to the stress test. Also, whether or not we consider this to be problem is a different matter. Possibly, if a certain error is very common it does not matter whether it is always larger or smaller than the correct solution.

Single-choice exercise: Improved version

Here, we continue to improve the exercise by randomly selecting only one of the two typical errors. Then, sometimes the error is smaller and sometimes larger than the correct solution.

err <- sample(c(err1, err2), 1)Moreover, we leverage the function num_to_schoice() (or equivalently num2schoice()) to sample the random distractors.

sc <- num_to_schoice(sol, wrong = err, range = c(2, 98), delta = 0.1)Again, this is run in a while() loop to make sure that potential errors are caught (where num_to_schoice() returns NULL and issues a warning). This has a couple of desirable features:

num_to_schoice()first samples how many random solutions should be to the left and to the right of the correct solution. This makes sure that even if the correct solution is not in the middle of the admissible range (in our case: either close to 0 or to 100), it is not more likely to get greater vs. smaller distractors.- We can set a minimum distance

deltabetween all answer options (correct solution and distractors) to make sure that answers are not too close. - Shuffling is also carried out automatically so

exshuffledoes not have to be set.

Finally, the list of possible answers automatically gets LaTeX math markup $...$ for nicer formatting in certain situations. Therefore, for consistency, the binomial4 version of the exercise uses math markup for all numbers in the question.

The corresponding stress test looks sataisfactory now:

s4 <- stresstest_exercise("binomial4.Rmd")

plot(s4)Of course, there is still at least one number that is either larger or smaller than the correct solution so that the correct solution takes rank 1 or 5 less often than ranks 2 to 4. But this seems to be a reasonable compromise.

Summary

When drawing many random versions from a certain exercise template, it is essential to thoroughly check that exercise before using it in real exams. Most importantly, of course, the authors should make sure that the story and setup is sensible, question and solution are carefully formulated, etc. But then the technical aspects should be checked as well. This should include checking whether the exercise can be rendered correctly into PDF via exams2pdf(...) and into HTML via exams2html(...) and/or possibly exams2html(..., converter = "pandoc-mathjax") (to check different forms of math rendering). And when all of this has been checked, stresstest_exercise() can help to find further problems and/or patterns that can be detected when making many random draws.

The problems in this tutorial could be detected with n = 100 random draws. But it is possible that some edge cases occur only very rarely so that, dependending on the complexity of the data-generating process, it is often useful to use much higher values of n.

Note that in our binomial* exercises it would also have been possible to set up all factorial combinations of input parameters, e.g., by expand.grid(p = 15:30, n = 6:9, k = 1:3). Then we could have asssessed directly which of these lead to ok solutions and which are too extreme. However, when the data-generating process becomes more complex this might not be so easy. The random exploration as done by num_to_schoice() is still straightforward, though.